The young man in the red bandana passed me three times in the tight confines of Cusco’s “Gringo Alley”, each time repeating his pitch, “Marijuana, cocaine, and Ayahuasca.”I wasn’t interested in the drugs, but I was curious. Everyone knows marijuana and cocaine but I wondered what the third one was. Ayahuasca, he told me was a drug with ancient and divine meaning to Andean people. He offered to be my guide into the spirit world; a trip that would give me enlightenment and wisdom. He claimed to be an Inca shaman. I declined this dubious offer of enlightenment, but became intrigued by Andean psychedelic shamanism.

Shamanistic healers operate openly in Peru and Ecuador, legally tolerated as cultural icons. They can be found throughout Latin America. They use herbal medications made from Andean and Amazonian plants to treat a range of illnesses, physical, mental, and spiritual. Chief among the substances in the shaman’s pharmacy is Ayahuasca (or Anahuac).

Taking mind altering substances like Ayahuasca, Psilocybin or Peyote induces visual imagery that, if interpreted with the proper insights, will open the door to awareness, triggering improvements and healing. A growing worldwide movement is holding Ayahuasca rituals in reverence as a path towards enlightenment. There is also a new tourist segment that travels for such experiences.

Alex Grey is an artist and the author of “Mission of Art”, a book about the meaning of images created by Peruvian shamans under the influence of Ayahuasca. The drug is a mix of plant essences including Banisteriopisis caapi, an Amazonian vine, as well as Charcuran and Pyschotiriai virdis, both hallucinogenic herbs. These are carefully measured and brewed into a tea. The correct dosage induces vomiting before the subject enters an extra sensory state of perception. Under the direction of an Ayahuasquero shaman, subjects have found insights that led to improved consciousness and relief from mental and physical anxieties and ailments.

Grey’s studies of plant sacraments of various cultures around the world have led him to conclude that these experiences are transcendently universal with religious overtones. In the Quechua language the word Ayahuasca means vine of the soul.

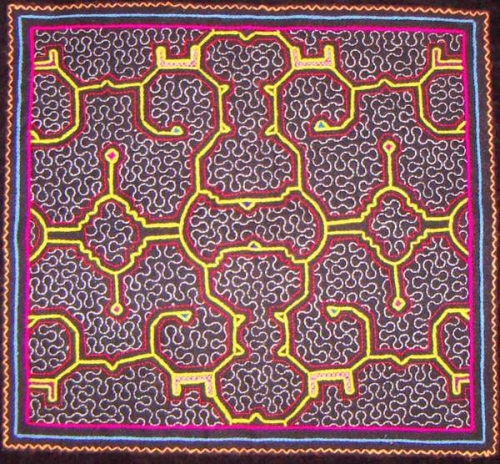

Grey says sometimes, “the doctor takes the medicine.” Then they create paintings resembling psychedelic art from the 1960s, with bright organic patterns. The artworks are made while chanting songs to induce a hypnotic state. The shaman diagnoses the imagery to prescribe a treatment of action for the patient.

Other healers have the patient ingest the Ayahuasca. Patient and healer talk it through to seek insights and tranquility. These unique treatments promise positive results for mental conditions like depression and substance abuse.

Ayahuasca is not a recreational drug, and it is used by skilled shamans to heal the mind. Some tourists look for shamanistic experiences merely for a trip. Where there is a demand there will be willing suppliers. As I learned in Gringo Alley, common street drug dealers will try to pass themselves off as shamans, possibly with dire results. Ayahuasca is a powerful substance and can be dangerous. No one should take it just for kicks.

A tourist who died after consuming Ayahuasca in 2012 triggered a wave of reaction. Authorities demanded a crack-down on the drug while a consortium of scholars (Ayahuasca.com) issued a defense, “Ayahuasca powerfully impacts both the body and spirit, and while a purgative, is non-toxic.

It must be facilitated in a ceremony by a person with extensive experience in all aspects of plant medicine, one who has studied for many years to understand the cultural traditions associated with Ayahuasca as well as the myriad physical and psychological effects this plant teacher will have on the seeker.

The facilitator, whether shaman, Ayahuasquero or Curandero, gringo or indigenous, should closely monitor and tend to the seekers’ spiritual, physical and emotional needs throughout the ceremony. The responsibility does not end there. The experience can be powerful, and at times disturbing, requiring support from the practitioner to help the seeker integrate the experience post-ceremony.”